How a dance superstar and an ancient Greece trend changed one Chicago girl’s life

There are two sides to every trend. First, you hear about the spangled celebrity who grabs all the press and gets credit on the Wikipedia page and in the history books, who is credited as the founder of a cultural movement and gets to mark it as one of their many achievements.

Then there are the people who follow.

In the 1900s, Isadora Duncan led what later became known as a classical dance movement. She was, without question, the biggest dance influence of her era. Drawing from classical dance and an idealized sense of ancient Greece, she spawned an entire subculture that wore robes, danced barefoot, and communed with nature and emotion while dancing. She remains an influential name in the dance world and even has an active company and foundation.

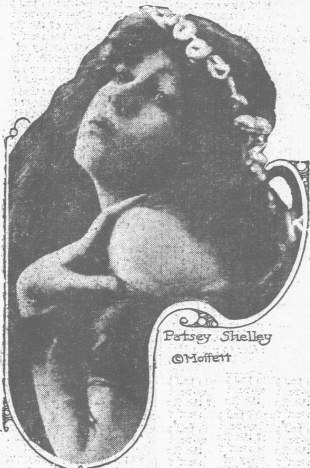

She has no institutes in her name and, to add insult to injury, no Wikipedia page.Then there’s Patsey Shelley (yes, that’s Patsey with an e). The possible great granddaughter of Percy Bysshe Shelley (or great grand-niece, depending who you ask) was a dancer in the classic Duncan style. In her day, she achieved fame and managed to become a small star in her own right. But she has no institutes in her name and, to add insult to injury, no Wikipedia page. But her role in the Greek dance craze shows, better than Duncan’s life could, how powerful the movement was. It was a way to find grace and beauty in a world where both were in short supply.

Patsey Shelley wasn’t born with a bow and arrow in her hand and a robe draped around her body. It had to get to her first. And when it did, it changed her life.

Isadora Duncan made dance pure and natural. And the world responded

Many books have been written about Isadora Duncan’s life and career. But it’s worth recapping how much she did.

Throughout her career, Duncan bounced between Europe and America, but it was her philosophy that stuck. She broke against rigid, pantomime-style ballet in favor of natural movement and improvisation. She made the explicit connection between dance and self-expression, and that started a movement. More superficially, she drew inspiration from classical dance, wearing Greek tunics and dancing in bare feet (both of which were considered scandalously revealing at the time). To Duncan, it was an aesthetic, but to many fans it was a fashion craze as well.

In the early 1900s, however, none of that mattered to a girl named Grace O’Ryan, because her father was dying of liver failure.

Grace O’Ryan finds tragedy too young

Patrick Shelley O’Ryan rose to great heights for an Irish immigrant, and he did it while maintaining his love of Ireland. After attending college in Dublin, he was labeled such an inspiring leader that he was offered a seat in the House of Commons. He declined it to come to Chicago and became an attorney. He quickly became an influential member of the community and earned a position on the School Board. He was the type of man people called both “level-headed” and a “fighter.” For a few months in 1908 he was dogged by unusual liver trouble, and on October 31, 1908, he died at 47.

She had a stunning ability to reproduce the lectures on Ireland that her father once gave.Nobody expected it—least of all his wife or daughter, Grace Patricia O’Ryan. They were at his bedside when he died, and Grace was just a girl. Three years later, she was still a young girl when she entered a scholarship contest in the Chicago Examiner to support her education. The Examiner said she had a stunning ability to reproduce the lectures on Ireland that her father once gave. The $7,500 prize would let her keep going to school.

She didn’t win.

A strange new trend takes off in New York

Meanwhile, Isadora Duncan’s movement was beginning to hit the mainstream.

In the summer of 1912, the New York Sun reported on the hottest fad in New York: Greek dance. It was clearly inspired by Duncan—one acolyte gushed over how Isadora Duncan once taught a child how to dance in time with the waves. But the movement had already become bigger than Duncan. Young women, and a few young men who dressed up as Pan, barefoot danced around the city, in parks and on rooftops, in scheduled performances and in improvisations. They took poses from Grecian art and made outfits to match.

Their dancing wasn’t limited to performances. Like yoga today, the fad became popular as a productivity tool. The Sun reported on one office worker who was tired at work and asked her employer if she could take a restorative dance break. She went to the roof of her building, danced in the fresh air, and came back to work with new vigor.

The trend was big enough that a socialite in Chicago heard about it.

A dance mentor takes on two new proteges

Jean Van Vlissingen claimed to have taught Isadora Duncan when Duncan moved to Chicago in 1896. Tellingly, Vlissingen doesn’t appear in any writing about Duncan, in her memoirs, or in any scholarship. Even if Vlissingen’s connection to Duncan was dubious, that didn’t stop her from taking on some local Greek-dancing proteges. One of them was Grace O’Ryan.

In 1913, Grace appeared in Chicago’s Daybook with a bow and arrow. Vlissingen failed to mention Duncan (instead, she promoted her supposed connection to Ernst von Feuchtersleben). But she did have a group of girls, including O’Ryan, who pranced around her yard in Greek garb with the goal of “coordinating” their bodies and souls. The article’s author noted that, fortunately, the yard where they practiced had a very high fence.

Grace and her friends did the occasional performance, including a dinner party in 1912. What seemed like a passing fad was really the beginning of a career.

A young dancer strikes out with a new name

Patsey Shelley O’Ryan, great grand-daughter of Shelley the poet, was one of the favorites. ‘Hail to thee, blithe spirit!’ quoted one of the older artists as she danced like a leaf across the lawn in The Dance of Joy—and she knew it.

The piece she performed was called The Dance of Joy. Coincidentally, in 1914 Isadora Duncan was performing a very different piece of her own.

Across the ocean, Isadora Duncan makes her Grande Marche

Isadora Duncan was back in Europe and she was mourning.

In 1913, her children Patrick and Deirdre were riding in the car with their nanny. They’d just had lunch. When the driver left the car to check on a mechanical error, he forgot to set the brake. It rolled down an embankment and into the Seine river. Both the nanny and Duncan’s children drowned.

Duncan’s piece, the Grande Marche, was her attempt to deal with the tragedy. Set to mournful Schubert, it featured a large group of dancers all trying to express Duncan’s grief. During the work’s first performance, Duncan sat in the audience pregnant with her third child, who later died a few hours after birth. Her movement, outlook, and approach had all changed, and she remained hidden in Europe.

But for Patsey Shelley, things were just beginning to pick up.

Patsey Shelley takes the world by storm

Van Vlissingen took Shelley and her friend, Roschen Turck-Baker, on a whirlwind tour. Their Greek style got press and attention wherever they danced. By then, O’Ryan had dropped her last name and was performing as Patsey Shelley. In Chicago, Shelley scandalized audiences with her bare legs, un-stockinged feet, and gauzy draping (supposedly, the police investigated the performance). In another show, Shelley delighted audiences by playing the muse of comedy.

The attention only grew in New York. Van Vlissingen eagerly promoted in the New York Sun, telling the interviewer that she’d taught Isadora Duncan and that Shelley was a relative of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Van Vlissingen said dance had aesthetic and medicinal benefits, and her girls exemplified both. She praised Shelley’s expressive hands and natural approach to dance. The girls were powerful stage presences even though they were only sixteen.

Shelley earned more notice when making her New York debut. The New York Theatrical Review called her “a Chicago dancer of growing celebrity…a sprightly young danseuse of the hoseless persuasion.”

Returning to Chicago as Shelley’s granddaughter

She performed Greek dances at the Blackstone Theatre in Chicago, playing the myth of Pandora. In the same year, she demonstrated a new dance at a church benefit: it was called the tango.

1915 continued the busy season with more performances and touring. She danced at a local restaurant once a week, but she also went as far as El Paso for a performance at the Alhambra Theater. While there, she led a group of several hundred dancers in a dramatization of a novel.

After that, Patsey Shelley’s career appeared to slow down. She was only in her teens at the peak of her fame, but the rest of the 1910s were without performances. She and her friends, like Roschen-Baker and another dancer, Yvonne Chappell, appeared sparingly as the Greek trend was waning. World changes, like World War I and the Russian revolution, were affecting the dance world and the wider culture.

Isadora Duncan herself became part of the new Russia, marrying poet Sergei Yesenin and performing frequently for party leaders. But her years after the deaths of her children weren’t easy. Reports of public drinking and debt tarnished her reputation. Her later years were unquestionably tragic. In 1925, Yesenin committed suicide. In 1927, Duncan died in a freak accident.

Patsey Shelley plays on

Fortunately, Patsey Shelley didn’t disappear.

The press notices are sparse, and there’s not a lot about the rest of her life and career. But in 1922, a “piquant young woman” hit Chicago stages with a backup band. By 1924, she’d shown up in Auburn, New York, a town a little outside of Syracuse.

She was there with a band of five players. The reviewer praised “the dancing and jazz band art of Patsey Shelley…Patsey Shelley is a dainty miss with great dancing ability. She is graceful and all her steps are new. Her costumes are unique and as attractive as the wearer…this act made a hit at the opening show last night.”

The review was for a type of show that was even more cutting edge than Greek dance.

It was called vaudeville, and Patsey Shelley was still on stage.